Owen and the 14th Indiana Volunteers chase the Confederates from the Battle of Gettysburg. Lincoln pulls the 14th from their pursuit to enforce the draft in New York after the New York Draft Riots. They enjoy "pleasant living" in the city. The battle-hardened and ragged soldiers present an oddity to New York society. After a quiet draft, they return to the battlefield.

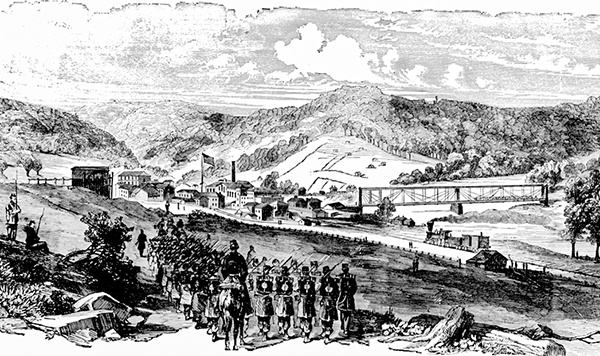

After their victory at Gettysburg, The 14th Indiana pursued the Confederates as they fled from Gettysburg, tagging them from Williamsburg to Harper's Ferry, to Elk Run, and finally to Warrenton. Minor skirmishing ensued along the way [1].

While the 14th marched and fought, Congress passed a conscription bill for drafting all able-bodied males between 20 and 45 years of age into the army. Republicans passed the conscription bill against strong Democratic opposition. The Democrats claimed that the Civil War was a rich man's war, being fought by the poor. The Democrats claimed a draft would force white working men to fight for the freedom of blacks, who would then come North and take jobs from the whites. The rhetoric from Democrats became a catalyst for anti-black and anti-Union violence that erupted throughout the North [2].

Draft riots become race war

In New York, a large Irish population was crowded in slums, with the worst disease mortality rate and the highest crime in the Western world. Most of the Irish were low-skilled workers making marginal wages. They were fearful of competition from black workers, and they were hostile toward the Protestant middle and upper classes. The Irish did not want a Yankee Protestant war for black freedom. They were ripe for revolt [2].

When the first draftees were drawn in New York, the Irish erupted. Thousands of men and women swarmed to the New York draft office, setting it afire and nearly killing its superintendent. Fueled by gangs, Tammany Hall, and anti-Union secessionists, concerns about the draft escalated to a full-scale war against blacks and the Union. Four days of indiscriminate looting and destruction ensued. The New York Times reported that rioters attacked, looted, lynched blacks, and burned an orphanage for black children. Also, rioters attacked businesses and business owners that employed blacks, Protestant churches, abolitionists, and supporters of the Union. Offices of Republican newspapers also fell victim to the mob violence. A pro-Union and anti-slavery newspaper, the New York Times headquarters was spared the fate of other Republican establishments because the founder and staff faced the mob with Gattling guns [4].

Uneasy peace for New York, "pleasant duty" for the 14th Indiana

With Federal militia and troops engaged in pursuing fleeing Confederates after the Battle of Gettysburg, mobs were too great for the New York police to stop. Abraham Lincoln's War Department pulled troops from the war to quell the rioters. On July 15 and 16, Federal troops fired into the rioting crowds, restoring an uneasy peace to New York [5, 3].

Another conscription was scheduled in New York for the first week in September. Lincoln decided to send troops to ensure a peaceful draft. To the delight and surprise of the men of the 14th Indiana, their Regiment was selected for the "pleasant duty" [6].

On August 21, Owen and his companions steamed up the Atlantic to New York Harbor and camped on Governor's Island. While they waited for the conscription, the front-line soldiers indulged in two weeks of big-city life.

A 14th Indiana soldier, John McClure wrote [3]:

…us boys are enjoying ourselves hugely. We landed on this island two days ago. I suppose we came here for the purpose of enforcing the draft in New York. We came here from Alexandria on the Steamer Atlantic. Had a long ride. Some of the boys got very sick, but I did not. We was on board of the ship for four days. Glad enough when we got on the island.

I think if we lay around New York very long, we will get fat. I can sit here on the grass in the shade and see New York & Brooklyn and Jersey City all just across the river from us. There is a lot of foreigners come in here by the shiploads every week.

The soldiers seemed to be more of an oddity to New Yorkers than New York seemed to be to the soldiers. Camped in Brooklyn, citizens freely wandered through their camp, gazing at, talking to, flirting with "the seasoned veterans of Gettysburg — like Mars, the war god, tamed," wrote 14th Indiana Soldier George Washington Lambert. "The most wealthy and aristocratic ladies come into our camp and walk and talk with the private soldiers. It seems as though the people have never seen any soldiers. Any number of them are young women" [6, p. August 28].

Once the draft was conducted peacefully, the 14th Indiana made their way back to their old division, steaming past Fortress Monroe, then marching through Virginia to Culpepper. Their first night back in the field, the 14th Indiana was pounded by a mid-September thunderstorm. Without tents, the soldiers dreamt of the Brooklyn ladies [7].

Recommended

References

|

[1] |

A. Connor, "Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, 1861 - 1865.," State Printer, Washington D. C., 1865. |

|

[2] |

J. M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, 1988. |

|

[3] |

J. R. McClure, Hoosier farm boy in Lincolns army, N. N. Baxter, Ed., Zionsville, IN: Guilde Press of Indiana, 1971. |

|

[4] |

New York Times, "The mob in New York: Resistance to the draft--rioting and bloodshed," New York Times, p. 1, July - August 1863. |

|

[5] |

New York Times, "Facts and incidents of the riot: The murder of colored people," New York Times, p. 1, 16 July 1863. |

|

[6] |

G. W. Lambert, Journal, Indiana Historical Society, 1863. |

|

[7] |

N. N. Baxter, Gallant FourteenthTraverse City: Pioneer Study Center Press, 1980. |

(C) 2020 by Brent Duncan, PhD. All rights reserved.