In the Summer of 1862, the War was not going well for the Union.

A thrashing of the Union Army at the Second Battle of Bull Run was just another in a string of Confederate victories against the ever-cautious George McClellan--despite far superior forces and resources. The rebels were riding high with ever-increasing confidence that triumph for the Confederacy was near. Momentum was on the side of the Confederacy.

At home, the Union troops had been driven from Virginia. Anti-war sentiment was strong in the North, fueled by anti-War Democrats and Southern sympathizers (both considered simply as traitors by the Union soldiers). Overseas, the English government felt the War had gone long enough—it was time to recognize the South as an independent nation.

Lee invades the North

Confederate General Robert E. Lee planned to take his momentum on the offensive and attack the Union on Union soil. In a letter to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee wrote,

“We cannot afford to be idle, and though weaker than our opponents in men and military equipments, must endeavor to harass, if we cannot destroy them.”

By harassing his enemy on enemy soil, Lee hoped to lure Union forces from Washington and ease Union pressure on the Confederate capital of Richmond. Since pro-Confederate sympathies were strong in Maryland, he decided to begin his campaign by giving Maryland “an opportunity of throwing off the oppression to which she is now subject.” He thought the abundant resources of Maryland—combined with a supportive populace—would sustain his hungry, tattered troops.

Lee also wanted to capitalize on the growing opposition to the War in the North. He felt an invasion of the North could strengthen the position of anti-war Democrats in the upcoming Federal elections. Lee also knew that a resounding victory in Northern territory could result in European recognition of the South as a sovereign nation. Such recognition could bring the Confederacy the material support it needed to offset the North’s superior industrial base.

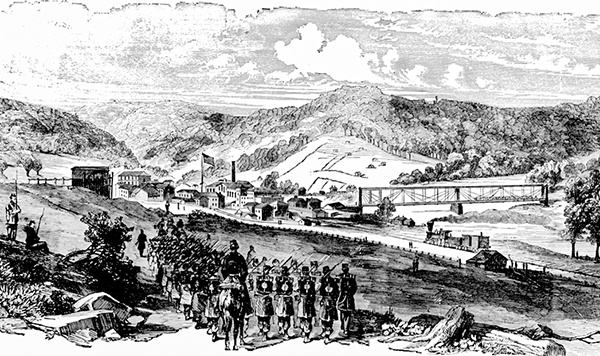

On September 3, the army of Northern Virginia—about 50,000 troops—broke camp and moved towards the shallow fords of the Potomac River. They crossed into Maryland for the beginning of what could have become a devastating sweep through Union.

News of the invasion reached Washington on the back of a horse. A Maryland farmer raced like Paul Revere down Pennsylvania Avenue, frantically shouting the news. Since the calamity at Bull Run a week before, Washington was in a state of panic.

England awaited the results of the Confederate invasion of Maryland before offering to negotiate a settlement between the North and the South.

Special Order 191

On September 13, two Union soldiers from the 27th Indiana set out in search of a spot for a noontime nap. What they found instead could have put an almost immediate end to the War. Wrapped around three expensive discarded cigars in an abandoned Confederate camp was a copy of Lee’s battle plans for the Northern invasion. The battle plans were immediately taken to George McClellan, General of the Union forces. Delighted over this immense stroke of luck, McClellan said, “With this paper, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home.”

If quickly acted upon, the discovery of Lee’s battle plans could have been devastating to the Confederate Army. But, characteristic McClellan, he faltered, triggering a series of tactical blunders and returning the upper hand to the Confederates.

Lee knew within 24 hours that the Union army had copies of his orders, and immediately regrouped his army.

Meanwhile, McClellan wired Lincoln that “Lee has made a terrible mistake." Then, again severely overestimating the size of his enemy by more than double, he hesitated another 16 hours. McClellan's hesitation allowed Lee to assemble his troops in Southwest Maryland, setting the scene for the War’s most horrible day.