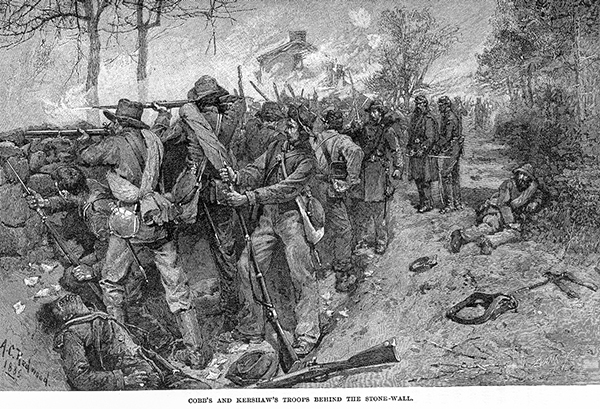

Jackson's troops were firmly entrenched and well protected behind a stone wall and in hedges and rifle pits at the top of the ridge. From their safe positions, the Confederates fired a steady stream of Minnie-balls into the dense lines of Federal soldiers struggling up the muddy slope. The barrage ripped apart the advancing Federals. Hundreds of Union soldiers fell with each volley.

A terrible battle: Fredericksburg

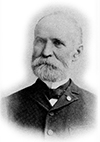

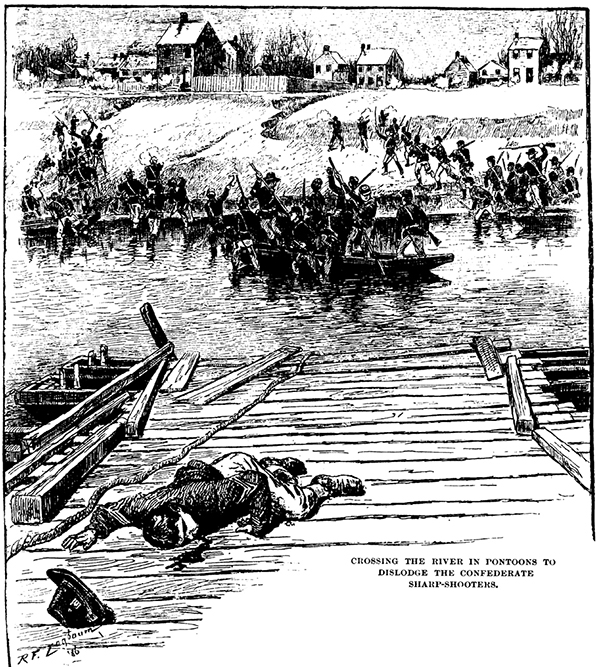

Pontoon bridge to death

The Army Corps of Engineers had the most dangerous of assignments.

On December 11 at 2 a.m., the engineers began hauling their pontoons into the freezing Rappahannock. Unarmed and exposed to fierce enemy fire, they had to position and secure the flat bottom boats in line, tie them together, then lay 400 feet of planking to the opposite shore.

The heavy Federal cannons attempted to drive off the sharpshooters who were picking off the bridge builders.

The fury of cannon fire laid Fredericksburg to ruins. But the Confederate sharpshooters held deadly aim.

In a final attempt to cover the bridge builders, four regiments crossed the river in pontoon boats. Within 30 minutes, the sharpshooters had retreated, and the engineers were able to finish their bridge.[1]

The 14th Indiana was one of the first regiments to cross the pontoon bridges into Fredericksburg to a march of death.

How beautifully they came

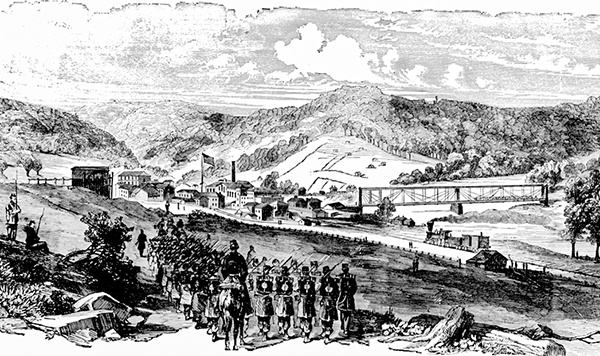

At 10 o’clock on the morning of the 13th, Kimball received orders to lead the advance on Fredericksburgh. The Gibraltar Brigade advanced on rebel positions north of the city. Under “murderous fire,” they were able to break through the initial Confederate defenses. But in an open field, just beyond Fredericksburg, cannonballs began raining on the tightly packed troops,[2] single shots reportedly killing up to 18 men at a time.[3]

Lee’s entire army stretched for five miles along a ridge looking down on the approaching Union troops. Burnside ordered Kimball’s men to attack the Rebel stronghold on top of a ridge called Marye’s Heights. The Gibraltar Brigade led the suicidal charge up the hill, Owen and the 14th, on the left near Telegraph Road.[4]

“How beautifully they came on!” wrote Confederate Lieutenant William M. Owen of the Washington Artillery of New Orleans. “Their bright bayonets glistening in the sunlight made the line look like a huge serpent of blue and steel. The very force of their onset leveled the broad fences bounding the small fields and gardens that interspersed the plain. We could see our shells bursting in their ranks, making great gaps. But on they came, as though they would go straight through and over us.”

Riddled by artillery fire, the brigade plodded up the hill.

Our poor fellows are falling

Jackson's troops were firmly entrenched and well protected behind a stone wall and in hedges and rifle pits at the top of the ridge. From their safe positions, the Confederates fired a steady stream of Minnie-balls into the dense lines of Federal soldiers struggling up the muddy slope. The barrage ripped apart the advancing Federals.[5] Hundreds of Union soldiers fell with each volley.[6]

Watching the massacre from the steeple of the court-house from above the haze and smoke, Major General Darius S. Couch shouted, “Oh, great God! See how our men, our poor fellows, are falling!” Men covered the field, prostrate, and falling. The living ran for cover but found none.[7]

Bloody and torn, the 14th found refuge in a sunken road on the field, 100 yards from the stone wall. Those who attempted to continue the assault were shot upon leaving the ditch.

They could not retreat even when ordered. Poised behind the wall on the ridge, Jackson's troops fixed their rifles on the sunken ditch where Owen and his companions lay. They riddled everything that moved: man, horses, even pigs and chickens that ambled across Telegraph road onto the field. Attempting to leave the shallow ditch meant certain death. Trapped, the 14th used the bodies of their dead companions as breastworks; they used up their ammunition and waited for reinforcements.[8]

Escape by storm

Against the advice of his officers, Burnside continued to order his troops up Marye’s Heights.

Wave after wave of Federal soldiers followed the 14th Indiana, but none could come close to where they lay. Confederate fire ripped apart each assault wave. The Federals could do no more than struggle along the base of the hill. Watching his troops annihilate the approaching Union forces, Lee said: “It is well that war is so horrible—else we should grow too fond of it.”

Under the cover of darkness and a fierce rainstorm, Owen and the others who made it to the ditch retreated one at a time, hoping the Confederates would not bother to fire on one man.[9]

That cold December night, 7,000 Federal soldiers lay dead or dying at the foot of Marye’s Heights. Many died from exposure, freezing solid as quickly as they died.[10] Confederate loss on Marye’s Heights was 1,200. The body of one 14th Indiana Soldier was found at the base of the wall.[11] Another had come within 100 feet before being struck down.[12]

In all, Burnside lost 13,000 men at Fredericksburg. Lee lost 5,300.

An army In despair

Summing up the slaughter at Fredericksburg, a Northern correspondent wrote: “It can hardly be in human nature for men to show more valor, and generals to manifest less judgment.”

The South was jubilant. The Union was despondent. Many in the North cried for a negotiated peace. Some cried for Lincoln to resign, saying he had surrounded himself with ignorant men, and that he was, in the words of Senator Zacharia Chandler, “too weak for the occasion.”

Burnside said the failure was due to the delay of his pontoons, but he assumed full responsibility for the debacle. In a letter to Lincoln, he wrote: “it is my belief that I ought to retire to private life.”

Not ready to reorganize his army again so quickly, Lincoln asked Burnside to remain.

References

[1]B&L 3 p 121-122. The Pontoniers at Fredericksburg.

[2]Kimball, Report of Gen. Nathan Kimball, U.S. Army, commanding First Brigade. Washington. D.C., December 22, 1862. The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 1861-1865. Fredericksburg.

[3]Goolrick, 76

[4]Beem, David E. War of the Rebellion, pg. 25.

[5]Cavins, E.H.C., Fourteenth Indiana Infantry. Report of Cavings, December 19, 1862. The official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 1861-1865. Fredericksburg.

[6]Goolrick, 77

[7]B&L 3, 113.

[8]Baxter, 117

[9]Baxter, 117

[10]B&L 3, 116

[11]Baxter, 118

[12]Longstreet, Lieutenant-General, C.S.A., C.S.A. B&L 3 p 81.

On the web: