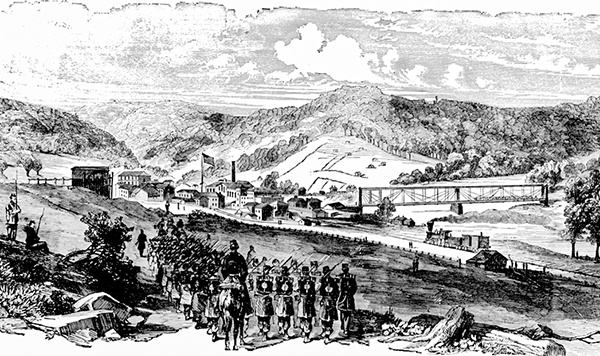

The taste of Battle at Rich Mountain made the youth of southern Indiana eager to “test their punk,” as Owen wrote. Instead, they marched to the outskirts of the Union Army in a desolate, rugged place called Cheat Mountain.

Related

- 02 Fearful retribution awaits them: Cheat Summit

- Surrounded on Cheat Summit

- Prettiest fighting ever: Battle of Greenbrier Bridge

- The severest campaign

Sprinkled amidst the rocks and laurel thickets on top of Cheat Mountain were the tents of 600 men, including Owen. The rest of the brigade guarded the bridge at Cheat River. Protecting the Staunton Road against a much larger Rebel force was not the adventure these men were seeking. Short rations, ragged clothes, discomfort from constant driving rain and cold, frustration from being far from the action, and boredom was about the only adventure they got (Beem, 2004).

The local mountain folks were staunch supporters of the southern cause. They thought little about “picking off” a Yankee whenever they had a chance. The locals’ intense hatred of the Union added a constant sense of uncertainty to the frustrations of the 14th Indiana soldiers.

Breastworks needed to be built to make the camp impassable—and to keep the men occupied. They dug ditches, stacked rocks, felled trees, pulled underbrush, built an impressive fort, and piled dirt to build the breastworks that would never see a battle.

With 10,000 Confederate troops stationed 15 miles away, daily scouting parties went out to cut up Rebel scouts, kill and drive pickets, and capture men and horses. Since the Confederate troops were doing the same, the scout and ambush parties were more like a deadly game of tag.

On one scouting excursion described by Owen, a small group from Company D was three miles from camp when they came upon 400 rebels. The 60 men from Company D gave a Hoosier yell and charged with bayonets fixed. The rebels, astonished at the sight of a few screaming men firing point-blank at their far superior force, could not organize. They ran for the safety of the forest.

This activity did little to ease the monotony of dormancy that gouged these men. Some took to reading scriptures, writing, or some other activity to “improve the soul.” Still, many became careless in search of adventure. They foraged for food, obtained meals from locals at gunpoint, and harassed mountain men and their children. Some even played hide and seek near rebel camps.

Morale was low. Petty bickering was common. Some threatened to resign. In one company, most non-commissioned officers and privates were thrown in the guard-house for mutiny. The men were ordered not to write about the matter (Beem, 2004).

In their test of battle at Rich Mountain, the men of the 14th Indiana had shown signs of being a cohesive and capable fighting force. In their test of patience, they started to rot (Baxter, 1980, pp. 65-66).

In describing their condition on Cheat Mountain, a 14th Indiana historian wrote the following:

“Their particular kind of fighting unit was like a blade: it functioned best in use. In its scabbard, the 14th rusted and tarnished into recklessness and even mutiny” (Baxter, 1980).

More glorious days would come for the men of the 14th Indiana than those spent on Cheat Mountain. Owen and his companions would go on to participate in some of the most furious, bloody campaigns of the Civil War. However, in the words of Captain E. H. C. Cavins, the 14th Indiana test of endurance at Cheat Mountain would be considered “the severest campaign of this company” (Cavins, 1884, pp. 120, 337-39).

Bibliography

Baxter, N. N. (1980). Gallant fourteenth. Traverse City: Pioneer Study Center Press.

Beem, D. (2004). History of the 14th Indiana Volunteers. David Enoch Beem Papers, 1821-1954. (A. S. Gressitt, Compiler) Indiana Historical Society Library.

Cavins, E. H. (1884). History of Greene and Sullivan Counties. Chicago: Goodspeed Brothers and Co.