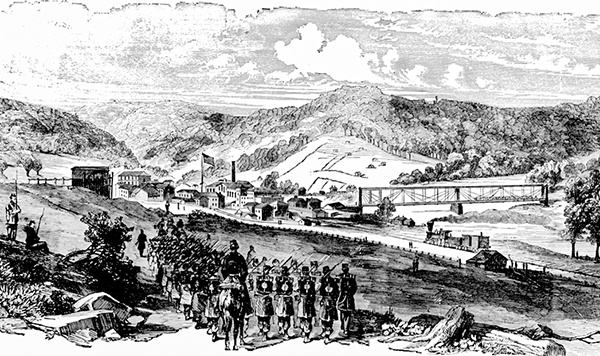

For four days, the army fought the weather. So heavy was the rain, so thick was the mud that wagons and livestock sank and became stuck and boots were sucked off by the mud. Across the river, the Rebels set up a signboard big enough for the Feds to see: “Burnside’s Army stuck in the Mud.”

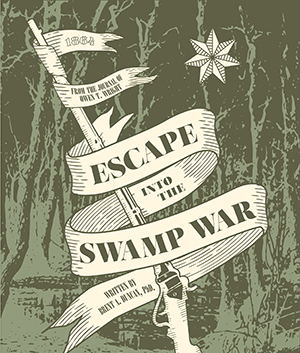

A terrible battle: Fredericksburg

The January 20 memo from Burnside referenced by Owen read as follows: “The auspicious moment seems to have arrived to strike a great and mortal blow to the rebellion, and to gain that decisive victory which is due to the country.” With that, Burnside informed his troops they would begin a march on Fredericksburg the following morning. To redeem himself, Burnside planned to march up the Rappahannock to an area where he thought the Confederates would not expect him. He would cross and attack a surprised enemy.

Dusk found Burnside’s troops slogging through dense fog and torrents of rain.

For four days, the army fought the weather. So heavy was the rain, so thick was the mud that wagons and livestock sank and became stuck and boots were sucked off by the mud. Across the river, the Rebels set up a signboard big enough for the Feds to see: “Burnside’s Army stuck in the Mud.”

“They were asking if we wanted any help laying pontoons,” wrote Private Alfred Davenport of the 5th New York in a letter home. “The rebels seem to know everything we are doing anyway and laughing at us.”

When the rain abated, the clearing skies exposed a beaten Army. They had advanced less than two miles in four days.

Defeated by weather, Burnside called off the offensive. Burnside’s weary troops returned to camp. Burnside’s second attempt on Fredericksburg would live on in infamy as the “Mud March.”

Burnside again offered his resignation. Instead of accepting his resignation, Lincoln reassigned Burnside to the Department of Ohio.

The Army of the Potomac would have another leader.