Writing that "this day will be a day-long remembered as being the most desperate day of fighting in which the 1st Brigade has witnessed" was accurate. Owen had fought in the most violent part of the bloodiest day of the Civil War. For withstanding the enemy while others ran, they had reversed the momentum of the battle, giving Lincoln the platform he needed to release the Emancipation Proclamation.

Advance toward retreat

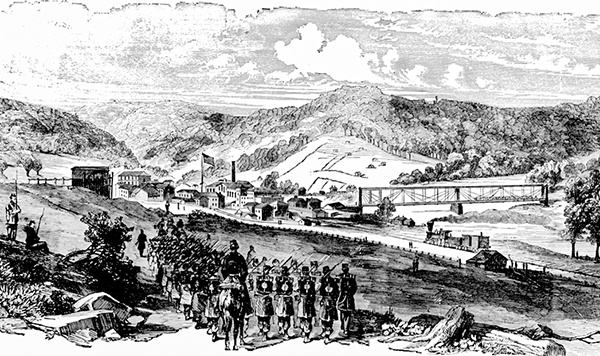

Outside the village of Sharpsburg, Maryland, Antietam Creek had been host to the bloodiest single day of the Civil War. Owen and the 14th Indiana had fought for a sunken road at the critical center of Lee's forces. Using the banks of the sunken road as a fort, the Confederates had obliterated wave after wave of Federal assaults. As the 14th waded across the waist-deep Antietam River and approached the battlefield, they faced a forest filled with unwounded Union soldiers escorting wounded men to the rear. This was a sign that discipline had failed. The battle was going poorly for the Union. [1]

The 14th Indiana marched toward the center of Lee's sharpshooters entrenched behind the banks of the sunken road. They faced an onslaught of bullets, cannon fire, and fleeing Union soldiers. The 14th taunted the fleeing soldiers, gave a loud yell, and approached the front lines. The assault of Confederate fire and troops became so high that the 14th Indiana received orders to fall back.

Their commander, Harrow, mounted his horse and screamed the order to retreat. The 14th Indiana Volunteers ignored him and fought their way to the edge of the sunken road across from the Confederates. Shooting at each other from opposite banks of the sunken road, they engaged in the most violent fighting in the most severe battle of the war. A few minutes later, Harrow again tried to give the order to retreat. The 14th Indiana fought on. Frustrated, he shouted, "Shoot God, Damn you, then!" Then, galloped to the rear looking for ammunition. [2] [3]

When the smoke cleared, bodies of fallen soldiers filled the sunken road. A Northern war correspondent described the scene as a "ghastly spectacle" where "Confederates had gone down as the grass falls before the scythe." [4, p. 684] The sunken road would become a lasting symbol of the horrors of the Civil War and Is know to this day as Bloody Lane. [5]

The capture of Bloody Lane cut Lee's center, he had nothing with which to patch it. One Confederate soldier wrote, "there was nobody of the Confederate infantry that could have resisted a serious attack." [6, p. 543]

A fresh Union Corps was eager to come behind the 14th Indiana and pounce on and finish off Lee's severely wounded and limping army. However, McClellan refused to attack in fear of the phantom Confederate reserves. Another chance to destroy the rebel army was lost. The following morning, only 30,000 Confederate soldiers remained alive and able to fight. In addition to having a force more than three times that of the Confederates, McClellan received fresh Union troops and supplies. Still, McClelland faltered. Lee escaped to Virginia. [1, 5]

A tactical victory

Though inconclusive, the Battle of Antietam was a tactical victory for the Union. Historians would consider it as a significant turning point in the Civil War. In addition to stopping Lee's first invasion of the North, the victory at Antietam accomplished two significant union objectives:

- First, the Union army had frustrated Confederate hopes to be recognized by Britain and France as a sovereign nation.

- Second, the victory at Antietam had given President Lincoln the platform to announce his Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all slaves and putting an end to the slave trade in the United States. [6]

At last, the North had an ideology behind their fight—they were fighting not only to preserve the Union but also to destroy the foundation of Southern slavery. The Union army was now fighting, in the words of Owen Wright, "in defense of the most sacred rights of freedom and humanity."

The Proclamation had a strong impact overseas, especially in Britain and France. Support for the South now meant support for slavery. "The Proclamation," said Henry Adams, U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain, "changed the whole character of the war and, more than any other single thing, doomed the Confederacy to defeat." [6]

The Union had succeeded in isolating the South from meaningful European assistance.

The Gibraltar Brigade

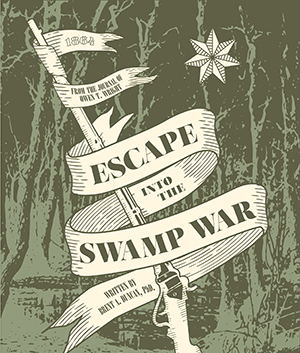

For their stalwart stand that turned the battle in the Union's favor, General French bestowed upon the 14th Indiana a sobriquet by which they would be known ever afterward: the Gibraltar Brigade.

Cannon fire continued through the night. Though many would not sleep, some died as shells descended on the camp of the 14th Indiana.

The 14th Indiana lost 210 men, over 50% of those sent to battle. [2]

And the War continues

History has not been kind to General George McClellan for his performance at the Battle of Antietam. The victory at Antietam was due to the fighting spirit of the Union soldiers, not due to the army command.

During the battle, McClellan's orders were both vague and slow. And he passed up many opportunities that could have put a quick end to the War (AH). He poorly fought the battle by allowing piecemeal and uncoordinated attacks of superior forces against the inferior enemy.

Though the inconclusive battle would be considered a Union victory, it could have brought the end of the War.

Bibliography

|

[1] |

F. W. Palfrey, The Antietam and Fredericksburg, The Archive Society Facsimile Reprint Edition, 1992 ed., New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1881. |

|

[2] |

N. N. Baxter, Gallant fourteenth, Traverse City: Pioneer Study Center Press, 1980. |

|

[3] |

A. H. Guernsey and H. M. Alden, Harper's pictorial history of the Civil War, Fairfax, VA: Fairfax Press, 1886. |

|

[4] |

C. C. Coffin, "Antietam scenes," in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 2-2 ed., New York, NY: The Century Company, 1887, pp. 682-685. |

|

[5] |

J. D. Cox, "The Battle of Antietam," in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Grant-Lee Edition ed., vol. 2 part 2, New York, NY: The Century Company Facsimile Reprint Edition, 1991, 1887, pp. 630-662. |

|

[6] |

J. M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, 1988. |