Burnside’s delay gave the confederate troops ample time to gather and confront their enemy. Daily, the Union soldiers watched the Confederate ranks swell to what Burnside would call “a vigilant and formidable foe.” While Burnside stalled, Lee gathered the entire Army of Virginia... President Lincoln and Burnside’s staff advised him to alter his plan. Colonel Rush C. Hawkins said to Burnside, “If you make the attack as contemplated, it will be the greatest slaughter of the war.”

A terrible battle: Fredericksburg

Desperate for good generals, Lincoln assigned Ambrose Burnside to command the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln chose the person who presented the fewest apparent liabilities to serve as his new general. In command of the Army of the Potomac, Burnside would prove to be obstinate, unimaginative, and unsuited both intellectually and emotionally for high command.

To his credit, Burnside understood his limitations; he freely confessed them. But his leaders didn’t listen. Expressing doubts about his abilities, Burnside reluctantly accepted his commission.[1]

Army reorganization

Burnside immediately reorganized the Army of the Potomac. He placed Generals Sumner, Hooker, and Franklin in charge of three “Grand Divisions.”

Owen and the 14th Indiana were under General Sumner.

Strategy

Having been long frustrated by McClellan’s inability to lead an offensive against the Confederates, Lincoln ordered his new general to attack—quickly!.[2]

Burnside presented a plan to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. He would first march his troops to the shores of the Rappahannock River, where they would build a pontoon bridge and attempt a crossing at Fredericksburg. Once beyond Fredericksburg, the Union Army would have a clear road to Richmond. He would have to march before Lee could block his path.[3] Lincoln approved the plan, sending a message that would prove ironic: “It will succeed if you move very rapidly, otherwise not.”

March

The maneuver started well.

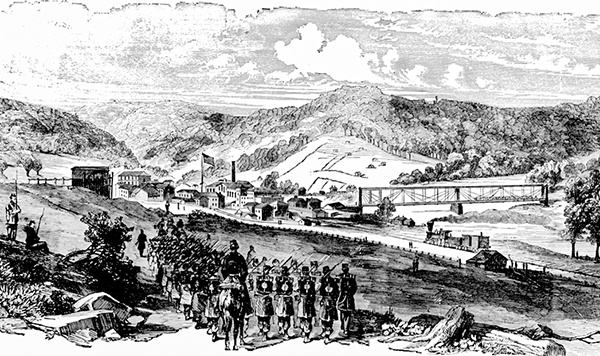

With Sumner’s grand division leading the way, Burnside ordered 117,000 troops through bitter weather to the shores of the Rappahannock River. By November 18, the entire Army of the Potomac was poised and ready to deal a severe blow to Lee’s army.[4]

Fredericksburg was only lightly defended. All Burnside had to do was march his army across the river, and the town would be in Union hands. A minor skirmish could result In a significant victory for the Union.

Lincoln's advice to "move very rapidly" did not sink in. Burnside hesitated and stalled for weeks.

Burnside waited over a week because the pontoons he felt were necessary to cross the river had not arrived, and he wanted to ensure secure supply lines.[5] After the pontoons had arrived, Burnside waited another two weeks before issuing the order to advance on Fredericksburg.

Confederate Operations

Burnside’s delay gave the confederate troops ample time to gather and confront their enemy. Daily, the Union soldiers watched the Confederate ranks swell to what Burnside would call “a vigilant and formidable foe.” While Burnside stalled, Lee gathered the entire Army of Virginia—72,564 strong— across the Rappahannock. Their line extended over five miles across the heights overlooking Fredericksburg.[6] Facing a superior force of 117,000 Union soldiers, the Confederates dug Into Impregnable positions.[7]

What should have been an easy Union victory over sparse Confederate troops had become the most massive confrontation of the war.[8]

President Lincoln and Burnside’s staff advised him to alter his plan. Colonel Rush C. Hawkins said to Burnside, “If you make the attack as contemplated, it will be the greatest slaughter of the war.”

Despite facing inevitable defeat, Burnside lacked the mental agility to alter his plans; he escalated commitment to the course of action that increasingly pointed to failure.

References

[1]Goolrick, William. Rebels Resurgent, pg29,30 (hereinafter referred to as Goolrick)

[2]Bowman, John S. Civil War Almanac, pp. 118-121.

[3]Battles & Leaders 3, 105.

[4]Civil War Almanac, 120

[5]Goolrick, 35.

[6]B&L 3 p 74. Map titled “Battle of Fredericksburg. Dec. 13, 1862.”

[7]B&L 3 p 97.

[8]Goolrick, 39.