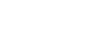

The 14th joined forces with General Joseph Reynolds, who had gathered ten regiments near the rebel camp at Greenbrier Bridge. Their purpose was to show their strength and reconnoiter, not to engage in battle. This was a disappointment to many in the 14th Indiana. They were eager to "test their punk," as Owen writes, or to take their turn to "show the rebels how to attack a camp," according to another soldier.

Related

- 02 Fearful retribution awaits them: Cheat Summit

- Surrounded on Cheat Summit

- Prettiest fighting ever: Battle of Greenbrier Bridge

- The severest campaign

A torrential ice storm made their movements impossible, delaying the surveillance. The Confederates had experienced the same when they attempted to attach Cheat Camp. J.T. Poole (1862, p. 45) wrote: "It seemed as though the storm-king had become angry with the puny efforts of the contending hosts and was about to settle the disputes in the wilds of Western Virginia by annihilating both parties."

Catching them by surprise, many of the 14th were without tents in the storm. Though some were able to squeeze into the tents of General Reynolds' troops, others slept in the rain. "Horses froze so disagreeable was the cold," Owen wrote. Many 14th India Volunteers suffered so much from exposure and frostbite that they could not join the action against the rebels at Greenbrier.

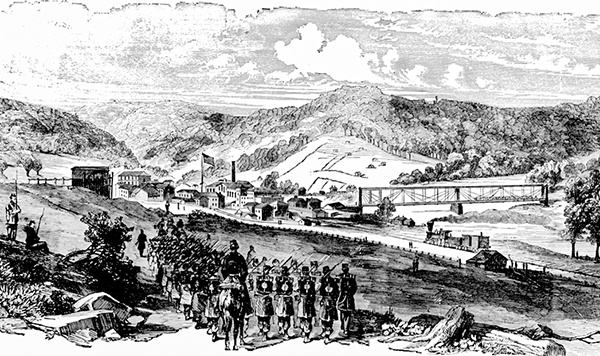

Considerable fighting and skirmishing occurred as General Reynolds drove back rebel pickets and outposts on the Union approach to Greenbrier Bridge on October 3. Owen described the engagement in his October 3 entry. After the rout of the Rebels, the 14th Indiana begrudgingly withdrew at the command of their officers. Colonel Kimball — and the rest of the 14th Indiana — had wished to charge the rebels. Kimball could not receive permission because General Reynolds did not want the action not exceed its objective of reconnaissance (Baxter, 1980). Reynolds' lack of action would perhaps be what was on their minds in future battles as the 14th Indiana developed a propensity for charging when commanded to retreat.

Regardless, the rout of Confederate troops allowed General Reynolds' command to gain valuable information about the strength and abilities of the enemy, as well as take possession of valuable horses and cattle (Long & Long, 1971)

An essential note to the victory at Greenbrier Bridge is that a spy from the 14th Indiana was in the rebel artillery. He hurriedly fed defused shells to the cannonaders (Baxter, 1980). His efforts took the wallop out of the rebel response. Unfortunately, his actions did not save Harrison Meyers, a private in Company H, when a defused cannonball lodged in his right hip (Poole, 1862; History of Owen County).

References

Baxter, N. N. (1980). Gallant fourteenth. Traverse City: Pioneer Study Center Press.

History of Owen County. (n.d.).

Long, E. B., & Long, B. (1971). The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861-1865. New York, NY, United States: Doubleday.

Poole, J. T. (1862). Under canvass, or, Recollections of the fall and summer campaign of the 14th Regiment Indiana Volunteers, Col. Nathan Kimball, in Western Virginia, in 1861. Terre Haute, Indiana: Oliver Bartlett. Retrieved from https://archive.org/embed/undercanvassorre00pool